The TUM Department of Mechanical Engineering has striven for the highest quality developments in engineering science since 1868. Our university was founded, among others, by refrigeration pioneer Carl von Linde and renowned mathematician and materials scientist Johann Bauschinger. It would become the base of Gustav Niemann, author of one of the most significant standard works in mechanical engineering, mechanic August Föppl and thermodynamics expert Wilhelm Nußelt. Former students include Rudolf Diesel who had the initial ideas for what would become his paradigm-shifting invention during one of Carl von Linde's lectures and the aircraft designers Claude Dornier and Willy Messerschmitt.

The industrialisation of continental Europe began in the early years of the 19th century. In Bavaria, too, factories and industrial companies were established. In 1848, Maximilian II, the third Bavarian king, took over the government. He promoted commerce and the industrial sector and founded the State Ministry of Trade and Public Works, the precursor to today’s Ministry of Economic Affairs. Bavaria experienced a veritable wave of industrialisation.

"The organic provisions for the new Polytechnic School in Munich have been granted approval by His Majesty the King, and the relevant royal ordinance will be published in the government gazette today." These were the words used by the Allgemeine Zeitung in Augsburg, one of Germany"s leading newspapers, when it announced the establishment of the Technical University of Munich (TUM) as a Polytechnic School on 24 April 1868 by Ludwig II, who occupied the Bavarian throne after 1864. This was also the date on which the history of today's Department of Mechanical Engineering began.

During its first year, a total of 24 professors and 21 lecturers taught approximately 350 students. The Allgemeine Zeitung continued: The school "comprises one general department and four technical schools: for engineers, architects, mechanics and chemical engineers. These five departments will teach both mathematical and natural sciences as well as the arts of drawing, construction and engineering, mechanical and chemical technology in their full scope."

The Department of Mechanical Engineering has its origins in the mechanics school, Department IV, Mechanical-Technical Department. There, knowledge about fundamental mechanical principles was to be gathered, expanded and disseminated. Specialists were to be trained with a specific technical perspective on the world.

At the time of its founding, theoretical mechanics was still part of mathematical physics at the General Department, and Technical Mechanics was part of the Engineering Department. This department dealt with geodesy, civil engineering and the field of infrastructure.

In 1877 the Munich Polytechnic School is renamed to Technische Hochschule München (Munich Technical University or THM).

After complicated negotiations with both the Bavarian and Prussian Ministries of Education the Munich Technical University is granted the right to confer doctorates in 1901 and is thus put on a par with Munich University.

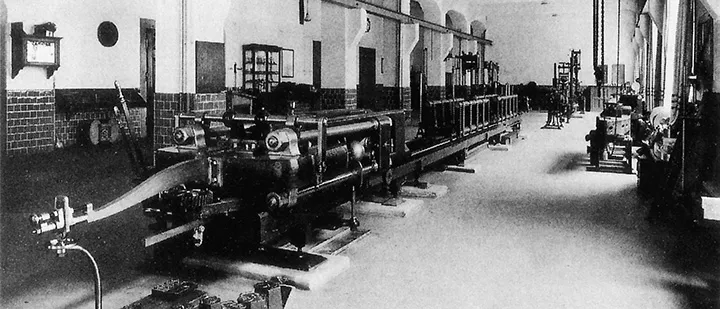

In 1871, Johann Bauschinger founded the Mechanical-Technical Laboratory which moved into a laboratory building of its own two years later. This later resulted in the establishment of the State Materials Testing Institute for Mechanical Engineering (MPA) which is located at the Chair of Materials Science and Material Mechanics now. Today the MPA regards itself as a service provider for the industrial sector, though Bauschinger’s original plan envisaged something different. From his perspective, the laboratory was intended above all to promote mechanical engineering research. It was only gradually that it began to be used differently. The original additional objective of inspecting materials and construction parts in exchange for money increasingly replaced the research activity.

In 1886, Johann Bauschinger published his study entitled: "On the changes of the elastic limit and of the strength of iron and steel caused by elongation and squeezing, by heating and cooling and by frequently repeated strain." He thus described the so-called "Bauschinger effect" later named after him, i.e. the change in the elastic limit of a metal or an alloy following a deformation which determines the direction.

Carl von Linde held the Chair of Theoretical Machine Science at the Munich Polytechnic School.

He established the Laboratory of Machine Science in 1875. With the newly-established Laboratory of Theoretical Machine Science the Munich Polytechnic School was ahead of all other German technical universities in scientific knowledge for nearly twenty years. The objective of this laboratory was to conduct various "proof-of-principle" studies in order to create better calculation principles. One of the first experiments concerns the determination of the properties of superheated steam.

For the first time, he also includes the theory of refrigeration engines and refrigeration technology in his field of teaching. Linde separated the teaching of mechanical engineering from machine construction and dividing the teaching into descriptive and theoretical mechanical engineering. While descriptive teaching overlapped with some areas of machine construction, the theoretical teaching of mechanical engineering comprised three focal content areas – kinematics, engines and mechanical heat theory. With this approach, Linde created the precursors of kinematics and hydraulics, refrigeration technology and thermodynamics as subjects.

While it was also originally intended as places of research and learning, the Laboratory of Machine Science quickly became a hub for inspecting and testing industrial products and providing advice to companies. Moritz Schröter in particular, who succeeded von Linde in 1879 and who was a distinguished expert in the field of technical thermodynamics, further expanded this main field of activity. The independent scientific work of the Technical University meant that industrial products obtained a type of quality seal after they had been inspected. Over the years, this became one of the department’s most important areas of work.

As well as testing the functioning of machines, the mechanical engineering professors also produced assessment reports. These could be presented as evidence in cases of dispute, technical failure or accidents, or patent proceedings. Linde stressed that: "For the lack of understanding among members of the patent office department in question, there is less to be gained from strictly physical proof (which they are unfortunately unable to comprehend) than through a certain explanation regarding the resulting facts of the case from an authoritative agency." Linde was convinced by the benefits of assessment reports. In a letter to his teacher, Gustav Zeuner, he wrote that the task of science was to assist in ensuring that justice prevailed with the aid of non-partisan judgements.

In 1880 Rudolf Diesel graduated with the best marks since the university was established and was awarded an honorary degree. During the first few decades of its existence students were given a report each semester like at a conventional school. Diplomas were only granted for "outstanding achievements" by the department on application. Only twelve diplomas were granted to graduates between the establishment of the school in 1868 and 1900.

Just how important the independent assessment reports of the university’s professors were for new developments was reflected in the story of Rudolf Diesel. When Diesel presented his engine, the innovative potential of his invention was confirmed by several professors – Schröter, Linde and Zeuner. Although Diesel’s thermodynamic predictions were incorrect, he received sufficient support for his invention from the industrial sector. This can be traced back in part to the major influence of the assessment report. In this report, for example, Carl von Linde emphasised that: "[I] can only confirm my view already expressed verbally to you, that the path you have taken is taking you directly and accurately to your goal of achieving the fuel consumption required for mechanical work which according to our current knowledge of physics and taking into account the current state of mechanical engineering should be regarded as the most ideally suitable." However, Carl von Linde noted that the calculations made by Diesel were too optimistic, and that, in the best scenario, a third of the value of the theoretical degree of efficiency calculated by him could be achieved.

August Föppl was professor of Technical Mechanics and Graphical Statics at the Mechanical-Technical Department (now Chair of Materials Science and Mechanics of Materials).

He succeeded Johann Bauschinger in 1894 and began to corroborate his theoretical work in the field of technical mechanics with practical experiments.

In 1897 the "Föppl" was released: August Föppl published the first part of his "Lectures on Technical Mechanics". The standard reference work was printed in numerous editions and remained the central textbook for mechanical engineering over decades. It is still published today.

In 1901 the first Chair of Electrical Engineering was established at the department. Electrical engineering was initially viewed as part of mechanical engineering. However, it grew increasingly more independent.

In the 1940s the name was changed to Department of Mechanical and Electrical Engineering. In 1948 the department was split into two independent parts consolidated in the department, one for mechanical engineering and the other for electrical engineering.

During the 1960s there were already discussions about the department’s separation into two independent ones. In 1974 the Electrical Engineering section finally became the Department of Electrical Engineering and Information Technology while the Department of Mechanical Engineering remained.

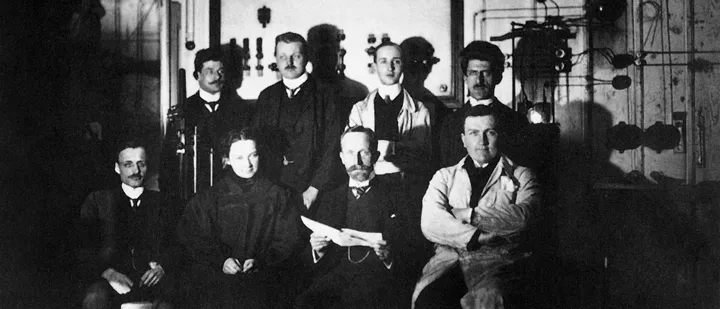

In 1902 Carl von Linde returned to the Munich Technical University as associate professor of Applied Thermodynamics. It is on his initiative that the Laboratory for Technical Physics was set up.

Since its establishment, the aim of the Laboratory for Technical Physics has been the experimental application of theoretically obtained knowledge.

Research was also carried out although the Technical University did not have an official research assignment. This teaching model set an example for many other technical universities and is applied to this day. The purpose of the laboratory was later explained by Wilhelm Lynen, Professor of Mechanical Engineering at the THM from 1909 onwards: "The student must deal with the machines himself, (…) he must see with an open eye, hear with his ear strained, feel with his hands, to understand how they behave when idling and under full load, at the highest speeds and at high temperatures."

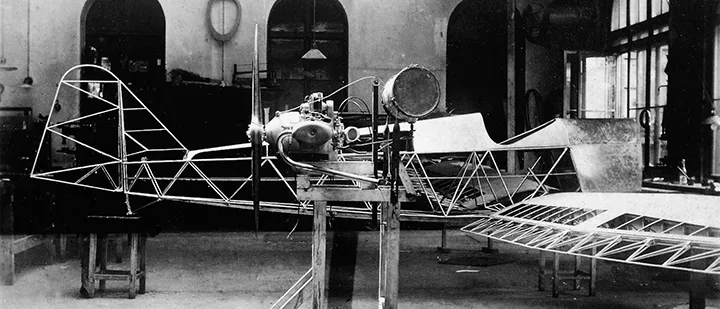

Willy Messerschmitt finished his studies at the Munich Technical University in 1923. In the same year he also came first in a gliding competition on the Rhön hills with his graduation project of a glider named "S 14". While still studying he already established the Messerschmitt Flugzeugbau GmbH in Bamberg which was incorporated into the Bayrische Flugzeugwerke AG (BFW) and renamed to Messerschmitt AG in 1938.

In 1930 Willy Messerschmitt was granted a lectureship on the construction and design of aircraft. He was appointed honorary professor in 1937 and in 1938 the Munich Technical University awarded him the honorary doctorate.

The Department was closely connected to the political and industrial development of Bavaria. In 1933, the Department of Mechanical Engineering – like the entire THM – became part of the Nazi system. The university was brought into line, partly by force, partly by conviction, partly out of anticipatory obedience; University members of Jewish origin were expelled, as were those with politically undesirable views.

In 1936 the Chair of Aircraft Engines and Engine Science was established under the direction of Kurt Schnauffler. During the following years a research institute for aviation and motor vehicle engines was set up at the Kapuzinerhölzl, north of the Botanical Gardens. The original plan to move the entire THM there was discarded because of the course of the war. Today the location at Schragenhofstrasse accommodates the engine laboratory of the Chair of Internal Combustion Engines.

From 1939 the department conducted research for the army, for example in the fields of torpedo propulsion, petrol injection and substitute fuels for car and aircraft engines. Non-military research was continued on a small scale.

In 1940 the Chair of Materials in Mechanical Engineering was carved out from Chemistry and was assigned to the Department of Mechanical and Electrical Engineering.

The Chair of Aircraft Construction was established in 1942 at the THM under the direction of Julius Krauß. From this time on, Lectures are held on the subjects of aircraft components, aircraft design, aircraft stability and in-flight measuring techniques, and research on these subjects is conducted.

In-depth arms research was carried out at the Chair of General Design Theory and Machine Elements which was established in 1935 under the direction of Erich Böddrich. The trial field, workshop, carpenter’s shop and test facility was extended and evacuated to Schäftlarn Monastery between 1942 and 1945.

Teaching and research activities practically grounded to a halt after the Second World War. Teaching at the THM was discontinued and the Chairs of Aircraft Engines and Engine Science and of Aircraft Design were closed down in 1945.

Both staff and students were involved in the reconstruction of the badly damaged university. Students teamed up in construction crews with the prospect of being given priority in re-enrolment in exchange for their help.

The "denazification" procedures at the THM initially caused the loss of two thirds of its university lecturers. There were 24 lecturers employed by the Department of Mechanical Engineering in 1945/46. Thirteen of these were dismissed, four of whom were reinstated by 1953.

Teaching at the THM was resumed again in 1946. About 3,000 students were accepted – most of them war veterans. Besides studying, the students had to commit themselves to fifty hours of auxiliary service work per semester.

In 1950 the Chair of Aircraft Engines and Engine Science which had been set up in 1936 was realigned and renamed to Chair of Internal Combustion Engines headed by Wilhelm Endres. Today, this chair still exists under the same name.

An enormous expansion took place in the 1950s and 1960s especially in process technology. Once the research ban in aerospace and production technology was lifted these areas likewise started thriving again.

In 1950, the Bavarian federal state government had already begun first discussions with the Allies regarding the resumption of aviation research. The German federal government was also highly interested in developing its own aviation and astronautics industry and research.

The Allied occupation status in the Federal Republic of Germany ended after the signing of the "Paris Agreements" in 1954. Now, German research could again participate in national and international aviation and astronautics projects. Julius Krauß, who had already been Professor Ordinarius for aircraft construction at the THM from 1942 to 1945, received the professorship for aeroplane construction, which was associated with an institute for lightweight construction and aviation technology.

In the years that followed, Munich became a centre for aviation and astronautics and the professorial chair for aircraft construction was further expanded – supported by the aircraft industry companies.

At this point in time, the professorial chair for aircraft construction was further expanded – supported by the aircraft industry companies. In Ernst Schmid, who in 1952 became Professor for Theoretical Mechanical Engineering and Technical Thermodynamics, the THM already had an expert in combustion processes in aircraft engines and temperature measurement at high flying speeds. He gained a reputation chiefly with his research in all fields of heat transmission, gas turbine design and water vapour research. The "Schmidt number" is named after him which describes the ratio between diffusive momentum transport and diffusive mass transfer.

In 1957, Erich Truckenbrodt was brought to the department, who had three new wind channels built for aerodynamics tests. During the 1960s the department put its focus on aerospace technology. The scientific council at the THM recognised the new opportunities presented by the political developments, and suggested that a professorial chair for astronautics should be established. In 1965/66 Truckenbrodt, who at that time was the dean of the faculty, then succeeded in having an institute for aviation and astronautics technology established at the department.

Gustav Niemann established the Chair of Machine Elements und the Gear Research Centre (FZG) in 1951. He held the chair until October 1968.

He worked in the fields of toothed wheels and gear manufacturing on which he published some pioneering works. His work "Machine Elements" in three volumes became a significant standard work in mechanical engineering.

In 1967, the Institute of Machine Tools and Industrial Engineering moved the focus of its research to information technology and production engineering.

The first microprocessors entered the market at the beginning of the 1970s. They opened up new perspectives for mechanical engineering and, during the following years, served as tools for significantly enhancing the possibilities in mechanical engineering. Processor-controlled machines enabled greater precision. Computer calculations and simulations sped up research and reduced its costs at the same time. The field of robotics emerged and the automation of even complex production steps was made possible. Information technology became an integral part of mechanical engineering.

In 1992, the Chair of Information Technology in Mechanical Engineering was established. This took into account the increasing significance of information technology in mechanical engineering. ‘[Our aim is] not only to utilise the potential for innovation connected with the arrival of information technology in mechanical engineering but to make the problems which accompany the new technologies controllable. Only if we succeed in this will our mechanical engineering be able to maintain its leading position’, founding professor Klaus Bender emphasised.

During the first decade of the new millennium the affordable computing power attained speeds which enabled a redesign, even the re-thinking, not only of communication and media but also of technology and, in particular, mechanical engineering. Computers were no longer just tools in mechanical engineering but became the core of previously unthinkable new applications.

For the first time, the TUM budget exceeded the threshold of one billion German marks in 1990. Almost 5,000 students were enrolled at the Department of Mechanical Engineering. The proposed relocation of the Department of Mechanical Engineering to Garching met with resistance from students. In June 1990 they staged a bicycle demonstration to point to Garching’s poor transport connection.

The construction of the department’s new campus in Garching was unique at the time – it was not public building authorities which carried out the project planning but BMW which was intended to speed up building. After a construction phase of only six years – and without exceeding the budget – the new department building on the Garching research campus with approximately 60,000 sq. metres floor space was inaugurated in 1997.

The building is aligned along a central covered axis which provides access to all chairs, the lecture halls, library, administration offices and the cafeteria. Its architecture follows an exact requirement analysis and is optimised for use as a place of research and study while exceeding the boundaries of the laws governing the construction of university buildings in force at the time.

Even the students of the department were involved in the building by designing the seating of the lecture halls.

In 2011, the department was the first institution at TUM to be evaluated. The assessors confirmed its outstanding research results. During the following years the department succeeded in considerably enhancing its scientific profile.

Under the project management of Markus Lienkamp, TUM presented the MUTE at the IAA Motor Show for the first time in 2011 – a joint project by 20 departmental professorships. The MUTE is solely electrically-powered. It has a maximum speed of 120 km/h and a minimum range of 100 kilometres.

In 2014, the TUFast student group designed the vehicle eLi14. It set the Guinness world record as "Most Efficient Electric Vehicle".

Nikolaus Adams has received the ERC Advanced Grant "NANOSHOCK – Manufacturing Shock Interactions for Innovative Nanoscale Processes" in 2015. This research project examines which mechanisms and properties enable the controlled formation of shocks in very complex environments – such as living organisms. These questions are to be studied and answered with the help of modern computer simulation models and some carefully selected experiments.

A new helmet-mounted sighting instrument developed by scientists at the Chair of Helicopter Technology was introduced in 2016. The "augmented reality" device enables helicopter operations in poor visibility, increasing the safety of both pilots and any passengers on board.

In 2017, the department set up its first cross-chair cluster "Additive Manufacturing". In addition to investments made by the chairs involved, the department contributed more than €500.000 in start-up aid to establish this pioneering topic.

Travelling from one place to another at almost the speed of sound – that is the idea behind the "Hyperloop Pod Competition" of visionary Elon Musk. Out of initially 700 teams, 30 teams were selected to build a prototype at the end in 2016. The WARR study group at the Department of Mechanical Engineering at TUM was one of these teams. In August 2017, the team won the maximum speed competition with its Hyperloop Pod II and established a new speed record with 324 km/h. In Juli 2018, the Team was able to increase the speed to 467 km/h with its new prototype and won the third competition.

In response to epochal technological upheavals in aerospace and geodesy, the Technical University of Munich established a new engineering department in 2018. The new Department of Aerospace and Geodesy (LRG) was officially launched on 1 October 2019 and combined the long-established expertise in aerospace engineering of the Department of Mechanical Engineering with fundamental research in satellite navigation, earth observation and basic geodetic disciplines.

The new department brings together many of the university’s established fields of expertise, spanning lightweight construction (fibre-reinforced plastics and carbon composites), drive systems, aerodynamics, control and sensor technologies, flight systems (air taxis), alternative energy sources (Ottobrunn algae cultivation center), satellite navigation, remote sensing, earth observation (ESA’s GOCE satellite) and all areas of geodesy.

The Faculty of Mechanical Engineering became the Department of Mechanical Engineering on October 1, 2021. It is thus part of the TUM School of Engineering and Design. The TUM School of Engineering and Design combines the former Faculties of Architecture, Mechanical Engineering, Civil, Geo and Environmental Engineering, parts of Electrical and Computer Engineering, as well as Department of Aerospace and Geodesy. Thus, in the context of an increasingly dynamic research and science landscape, TUM is systematically developing its transformation process with Agenda 2030. Following international best practice approaches, TUM is pushing ahead with a fundamental reform to convert the faculty system to an innovation-promoting matrix organization of schools and departments as well as interdisciplinary research centers (Corporate Research Centers, Integrative Research Centers). With the start on October 1, 2021, TUM will create design opportunities in research, teaching and entrepreneurship, dynamize interaction potentials and, in doing so, preserve the academic diversity and value-giving specifics of individual subject cultures. Bringing different faculties together in the School facilitates cooperation and the strategic adoption of innovations in engineering and design. Supportive management and administrative structures at the school level lead to further quality improvements and faster internal processes, as well as to a reduction in the workload of the scientists.